on Blogcritics.

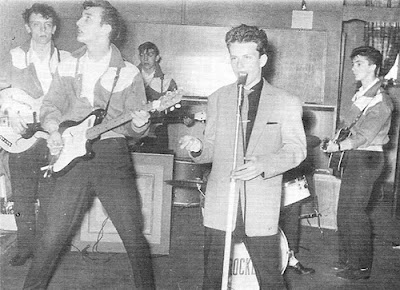

Otis Redding, Buddy

Holly, James Dean, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Amy

Winehouse, John Bonham, Robert Johnson, Hank Williams, Keith Moon, Kurt Cobain,

even Sam Cooke - Just many of the musical legends who died young and became

instant cultural icons. We have a perverted fascination with those who create a

special body of work, then pop their clogs before they get a chance to tarnish

their reputation.

Many died as a

result of depression and/or substance abuse, others simply as a result of being

in the wrong place at the wrong time. Stuart Sutcliffe, the original bassist

with The Beatles, joined this tragic and iconic club in April 1962.

Sutcliffe’s iconic

status was assured almost instantly after his death from a cerebral haemorrhage

on April 10th 1962. His legend is perpetuated not only by his

membership of the most famous group in the history of popular music,

particularly during their most uninhibited and formative period, but also by

his own independent talent and good looks.

His close friendship with one half of the 20th century’s most celebrated

composers, as well as his battles with the other half, have guaranteed that his

name is forever inextricably linked to those

of Lennon-McCartney and The Beatles. Indeed Sutcliffe receives credit for

conceiving the group’s name. In addition, the details of his tragic love affair

with a beautiful German fiancée who helped to shape the groups early image, and

his premature death at the age of 22 make for a fascinating story that writes

itself perfectly for a film script...and it has.

No fewer than three

movies have documented Sutcliffe’s life, most famously the 1994 film BackBeat. However, as early as 1979, the

film Birth Of The Beatles placed more

emphasis on Sutcliffe’s character than that of McCartney or Harrison. In addition

to these movies, Sutcliffe has been the subject of some four documentaries and at

least five books.

Despite this

however, his contribution to The Beatles has often been conveniently played down.

Sutcliffe was the musically-bereft, James Dean wannabe who was relieved of £65,

and selfishly press-ganged into Lennon’s group to provide a back-beat on an

instrument he couldn’t play anyway, right? Well, perhaps on the 50th

anniversary of his tragic death, this young man’s legacy deserves a second

look.

Stuart Victor

Ferguson Sutcliffe was born June 22nd 1940 in Edinburgh, Scotland to

middle class parents. His father, like John Lennon’s, spent the greater part of

the war away at sea. The small, effeminate and sensitive Sutcliffe left Grammar

school, and with a burgeoning talent for drawing and painting was enrolled at

the Liverpool College of Art in 1956 at 16...two years earlier than the average

age of enrolment. Moving in Liverpool 8 art school circles, he was introduced to

John Lennon sometime in 1957/58 by fellow student Bill Harry, who later founded

the paper- Merseybeat.

On the surface

Lennon and Sutcliffe appeared to be polar opposites. Lennon was already highly

skilled at hiding his emotions behind a firewall of aggressive and abusive

cruelty towards anyone on his radar. This behaviour moved up a gear at Art

College as a defence mechanism to deflect from the fact that he believed

himself to be a phony who was in over his head and surrounded by real talent.

When it came to applying himself to his studies he was lazy, bored and easily

distracted...the worst pupil in his class. Sutcliffe on the other hand was

gifted with a natural talent for drawing, painting and even sculpture. He was a

determined, studious, and meticulous artist who possessed an intensity and

dedication which alarmed his tutors. Well aware of the young man’s artistic

promise, his tutors allowed him to work from his flat although they asked him

to slow down and take life easier even then.

Sutcliffe was the

most promising student at the college. Cynthia Powell, John Lennon’s future

wife and art school student remembers Sutcliffe’s nature as being opposite to

Lennon’s completely. “Stuart was a

sensitive artist and he was not a rebel, as John was. He wasn’t rowdy or rough”.

(Mojo, 10 Years That Shook The World p.26)

Despite their

differences however, they possessed a mutual admiration for each other, and for

rock n roll. Unlike his jazz influenced art school contemporaries Sutcliffe was

influenced by Elvis, which intrigued Lennon, and it was rock n roll's imagery

that drew him to Lennon’s group.

Lennon was intimidated

by Sutcliffe's talent and particularly by his image. Sutcliffe however also

admired Lennon's cartoons, particularly their honest and satirical subject

matter.

Sutcliffe’s praise

of his work had the effect of making Lennon feel he actually belonged at the

art college. He also fulfilled Lennon's desire to be taken seriously by a

serious artist whom he looked up to. Sutcliffe flattered Lennon and fulfilled

an early role as a muse, a role later occupied by Yoko Ono. Indeed Sutcliffe

introduced Lennon to Dadaism, a

movement Lennon would later embrace wholeheartedly during his peace campaigns

with Ono.

Arthur

Ballard, a former tutor at the Art College commented that "without Stu

Sutcliffe, John Lennon wouldn't have known Dada from a donkey" (Philip

Norman, Lennon – The Life p.136)

Late in 1959, Lennon’s

group sought to broaden their prospects for bookings with the addition of a

drummer and/or bass player. Lennon allegedly tendered either role to Sutcliffe

and fellow flatmate and art student Rod Murray, who set about building a bass

made from college materials. He was beaten to the role however by Sutcliffe who

purchased a bass guitar sometime in early 1960 with £65 he made from the recent

sale of a painting which had hung at exhibition in the prestigious Walker Art

Gallery.

The general myth

has always held that Sutcliffe was led astray by Lennon and the others, and

duped into spending his money on the band. Quite the contrary however, it seems

that Sutcliffe was a willing and enthusiastic addition to the group. Bill Harry

claimed that the image of being in a rock n roll band appealed to Sutcliffe

more than the music itself, (Norman, Philip, Lennon, The Life p.168) and it

became an extension of his own moody image. Lennon certainly approved,

dismissing Sutcliffe’s early struggles with his new oversized instrument by setting

his priorities straight and declaring; "never mind, he looks good" (Norman,

Philip, Lennon, The Life p.237). George Harrison recalled that it was better to

have a bass player who couldn’t play, than not have one at all (Anthology).

Not everyone

approved though. Paul McCartney smarted at his demotion in the ranks as a

result of Lennon and Sutcliffe’s friendship and he admitted years later that 'the

others' were jealous of the relationship, feeling they were forced to take a

back seat (Anthology). In fairness, his dislike of the situation was also due

to his frustrations with Sutcliffe’s musical ability. Even at this early stage,

the idealistic differences between Lennon, whose ethos was ‘let’s play’, and

McCartney who leaned towards ‘let’s play it right’, were plain to see. Yet, it

was the subtle marriage of these contrasting ideologies which would make their

partnership so devastating throughout the decade.

So enthusiastic was

Sutcliffe for his new life as a rock n roller, that he began writing to booking

agents on behalf of the band, and signed himself as – manager. Does that sound like the actions of a talented artist with

a bright future, who was cajoled into parting with his money and joining a

musical group with little prospects?

Sutcliffe’s next

contribution to the group was to prove to be his most enduring. Still uncertain

of their artistic moniker, (The Quarrymen had Become Johnny and The Moondog’s),

Sutcliffe suggested The Beetles in homage to Buddy Holly’s Cricket’s. This name

evolved several times through Beetles, The Beatals, The Silver Beetles, The

Beetles and finally, The Beatles.

In May 1960, the

group famously auditioned to become a backing band for Billy Fury, but instead

ended being assigned a drummer and embarking upon a budget tour of Scotland

with Liverpool singer, Johnny Gentle. The tour was an eye-opener and a disaster

for many reasons. For Sutcliffe however it revealed that the life of a musician

was not necessarily glamorous, and that his friendship with Lennon was far from

perfect.

Unable to compete with Sutcliffe's artistic

abilities at college, Lennon seemed to enjoy becoming his friend’s artistic

superior once he strapped on a bass and stepped on-stage.

Lennon admitted

that he was particularly cruel to Sutcliffe during the tour, refusing to allow

him to eat or even sit with the others. He belittled his friend’s height and

zoned in on his struggles with the Höfner bass he wore.

By the time the

group acquired permanent drummer Pete Best in August 1960, Sutcliffe found

himself bound for Hamburg to play rock n roll in the sleaziest of Europe’s red

light districts. He had horrified his family and tutor’s by abandoning his

teacher training diploma and turned his back on his art completely. However he

was held in such high regard by the Liverpool College of Art that they agreed

to keep his place open for his return, if and when he saw fit. For the others,

no such friendly offers lay open...Hamburg was make or break.

Soon after his

arrival on the Grosse Freiheit Sutcliffe had met, fallen in love with and

become engaged to a beautiful German existentialist by the name of Astrid

Kircherr. Unlike the typical female fan, Kircherr was not only beautiful and

stylish, but confident, cultured and a talented photographer.

The group were far

from irritated by Sutcliffe’s new found love, in fact they encouraged it.

Kircherr’s family acted somewhat like the Asher’s later did for Paul McCartney.

Mrs. Kircherr, appalled by the group’s living conditions in St Pauli, allowed

Stuart to lodge in the loft while often tending to the rest of the group;

washing their clothes and providing hot meals. Astrid’s affections and

admiration for Sutcliffe’s talent woke him from his rock n roll coma and ignited

his interest in art again. She and her friends also appealed to the

existentialist in him, and it wasn’t long before he was dressing just like his

new German friend’s. In another vital building block to the group’s image and

direction, Sutcliffe became influenced by Hamburg’s existentialists clothing

and hairstyles, and through him, so too did The Beatles.

The group were far

from irritated by Sutcliffe’s new found love, in fact they encouraged it.

Kircherr’s family acted somewhat like the Asher’s later did for Paul McCartney.

Mrs. Kircherr, appalled by the group’s living conditions in St Pauli, allowed

Stuart to lodge in the loft while often tending to the rest of the group;

washing their clothes and providing hot meals. Astrid’s affections and

admiration for Sutcliffe’s talent woke him from his rock n roll coma and ignited

his interest in art again. She and her friends also appealed to the

existentialist in him, and it wasn’t long before he was dressing just like his

new German friend’s. In another vital building block to the group’s image and

direction, Sutcliffe became influenced by Hamburg’s existentialists clothing

and hairstyles, and through him, so too did The Beatles.

Kircherr also took

some iconic shots of the group, and her style was copied verbatim for the cover

of their second LP; With The Beatles,

which was considered an artistic watershed in terms of album covers.

Following the deportation

of Harrison, McCartney and Best in late 1960, Lennon also headed for home

leaving Sutcliffe behind with his fiancée. He had by now lost interest in his

rock n roll career and intended on taking up his studies again. Back in

Liverpool the Beatles career began to take off following their first

apprenticeship in Hamburg, and for a time they adapted a new bass player; Chas

Newby, who later left of his own accord. In December of 1960, Harrison also apparently

asked John Gustafson, bassist with The Big Three to join The Beatles...Gustafson

declined, understandably a decision he lived to regret.

When Sutcliffe

returned to Liverpool in February 1961 he headed straight for the Art College,

committed to picking up where he left off. To his dismay he found the door firmly

shut to him, regardless of his golden promise. The reason for his banishing was

later discerned to be his suspected role in the misappropriation of a student’s

union amplifier; a Selmer Truvoice amp which was almost certainly ‘borrowed’ by

The Silver Beetles. Disgusted and desponded, Sutcliffe returned to Hamburg in

March 1961 to be with his fiancée and to test the possibilities of studying

there. On application to the HFBK, or Hamburg College of Art, Sutcliffe made

such an impression on Scottish-Italian artist and tutor Eduardo Paolozzi that

he was immediately enrolled and given a generous grant. Sutcliffe soon picked

up where he had left off in Liverpool by painting in the loft of the Kircherr

house in Hamburg and, here his and the Beatles paths began to diverge. He still

occasionally played and sang with the group during their second Hamburg

residency, but McCartney had by now largely taken over on bass.

By October 1961

Sutcliffe was suffering from blinding headaches and dark mood swings, often

coupled with aggressive bouts of unprovoked jealousy towards his fiancée. He

was eventually persuaded to see a doctor who diagnosed nothing but a

troublesome appendix and advised Sutcliffe to slow down, rest and quit

cigarettes and alcohol.

Early in 1962 his

health declined further and he began suffering seizures. He was eventually

diagnosed as suffering from increased cranial pressure and this was temporarily

relieved by a treatment of cranial hydrotherapy. Sutcliffe and Kircherr visited

Liverpool in February 1962, where friends noted his alarming weight loss and

more than usual pale complexion.

During this visit

he met Brian Epstein, the new Beatles manager, and discussed a future role as

an artistic director and designer for the band. Predictably, Epstein was drawn

to Sutcliffe's looks and later wrote to him in Hamburg that he “[...] didn't

know anyone as lovely as you existed in Liverpool". (Norman, Lennon - The Life

p.262)

Upon his return to

Hamburg, Sutcliffe’s seizures and mood swings escalated. He wrote home that “[his]

head was compressed, and filled with such unbelievable pain". (Norman,

Lennon - The Life p.262) On April 10th 1962 he suffered an hour long seizure at

his home and fell into a coma. Despite being rushed to hospital by ambulance

Sutcliffe died during the journey, rested in his fiancées arms.

The next day, unaware

of his death, the Beatles minus George Harrison, flew out to Hamburg from

Manchester to begin yet another engagement. They were greeted by a distraught

Kircherr in the arrivals hall, and her news sent Lennon into aggressive

hysterics.

Lennon was later

criticised by the Sutcliffe family however for his lack of emotion over his friend’s

death.

The show of emotion

in Hamburg airport had evaporated - or been carefully withdrawn - by the time

his friend's mother arrived (on the same flight as Harrison and Epstein) the

following day. Lennon in his defence was 21 years old, hardly a matured man,

and those young years had already seen their fair share of trauma. Already aware

that his father and mother had abandoned him, death had been a frequent caller

to his door what with losing his surrogate father (Uncle George) at 15, his

mother at 17, and now his best friend at 21. It's little wonder that he

developed an aggressive defence mechanism for bottling and hiding his emotions.

There are enough clues throughout his life however to suggest that he was

always haunted by the death of his best friend and perhaps his frequent cruel

treatment of him in public. Kircherr felt his behaviour towards Sutcliffe was

another of his defence mechanisms; “I’m thinking when he treated him badly, it

was because he was afraid anyone might see how much he loved him” (Norman,

Lennon – The Life, p.214).

Sutcliffe may have

been the subject of the confessional, self-healing and melancholy Beatles song

'There's A Place', composed the same year as Sutcliffe's death. He was also

certainly one of the central subjects in Lennon's 1965 autobiographical 'In My

Life', and his friend also ensured that Sutcliffe finally made it onto a

Beatles album; standing among the greats of the 20th century on the cover of

the group's magnum opus - Sgt. Pepper’s

Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Yoko Ono has also maintained that Lennon

spoke of Sutcliffe every day throughout his life, so much so that she felt she

had known him herself.

Controversy has

surrounded Sutcliffe in death just as it has his deceased best friend. His

death was deemed the result of a cerebral haemorrhage, but post mortem results

pointed to a previous skull trauma, possibly the result of a blow...or a kick. Beatles

myths often have a tendency to grow into monsters and Sutcliffe’s death is no

exception. Not surprisingly, views on how Sutcliffe may have been injured

differ enormously.

The famous story is

that Sutcliffe was ambushed and violently kicked in the head by a group of

youths following a gig at Lathom Hall. This is the story put forth by Philip

Norman, author of Shout!, and Lennon – The Life. Norman states the

incident occurred in early 1961, probably Feb 25th. He also states

that Sutcliffe’s mother found him that night, bleeding heavily from a head

wound.

However, Bill

Harry, Pete Best and Neil Aspinall maintained that the incident had occurred on

May 14th 1960, and that it involved a few punches and nothing at all

as sinister as a kick to the head. Best recalled; “When people talk of Stu

being beaten up, I think it stems from this incident. But I don’t remember Stu

getting to the stage where he had his head kicked in, as some legends say,

alleging that this caused his fatal brain haemorrhage” (Mersey Beat Archives).

The trouble is,

neither Pete Best nor Neil Aspinall worked with the group in May 1960. They

were both with The Beatles by February 1961 however, the time the incident

occurred according to Philip Norman, although their recollections seem to

refute the viciousness of Norman’s description of events. Time has muddied the

actual details it seems, but what probably occurred is that a minor fracas took

place in February 1961, which involved no serious head injuries. Incidentally

Sutcliffe only returned from Hamburg in late February 1961. So if he was with

the group at this performance, it must have been one of his first engagements

upon his return.

The Sutcliffe family have thrown further fuel on the fire in the debate. In her book The Beatles' Shadow: Stuart Sutcliffe & His Lonely Hearts Club, Sutcliffe’s sister Pauline claims that on his final return to Liverpool her brother told his mother how John Lennon had attacked him in a drunken rage, knocking him to the ground and kicking him repeatedly in the head. The incident was supposedly fueled by his jealousy of Stu, and his ever increasing frustrations with his musical abilities. Paul McCartney was cited as the sole witness, and it was allegedly he who carried a bleeding Sutcliffe back to his digs. The incident was kept in the Sutcliffe family until 1984, thus denying Lennon a chance to comment on the allegation of any involvement in his friend’s death.

Lennon was known to have a violent streak, sure, and he was a famously mean drinker. However the alleged attack is largely out of character with his documented relationship with Sutcliffe, and indeed the rest of his band mates. There are well known stories of John Lennon going on-stage wearing a toilet seat, urinating from balconies, mugging sailors, and walking the streets in his underwear. So, surely a story of him administering a vicious beating to his best friend in public would be supported by someone who was there.

Horst Fascher, the group’s unofficial bodyguard in Hamburg and a man for whom violence was a working tool, claims he never heard of such an incident. Sutcliffe himself, a man who wrote letters home frequently, never wrote of the incident, and neither Harrison nor Best has ever mentioned it. Astrid Kircherr, his fiancée claims that Lennon never raised his hands to Sutcliffe, dismissing the allegation as “rubbish”. (The Lost Beatle, BBC 4 Documentary)

McCartney, who

supposedly witnessed the incident, has no recollection of it, although he

admitted that John and Stuart could

have had a drunken fight (Anthology).

As always, analysis of recollections should be subjected to a degree of

scepticism, owing to the sheer amount of time that has elapsed, not to mention

the tricky issue of disentangling personal agenda.

McCartney has

always come-off as a villain in Sutcliffe's story. The one well documented on-stage

punch-up involving Sutcliffe was with McCartney, supposedly the result of an

unkind comment aimed at Astrid Kircherr. He made no bones of his opinion on

Sutcliffe’s, and even Best’s musical abilities, once shouting at them both during

a performance; “You may look like James Dean and you may look like Jeff

Chandler, but you’re both crap.” (Norman, Lennon – The Life, p.237)

McCartney has

confessed that he was jealous of Sutcliffe, the older boy, and no doubt

Sutcliffe's image and artistic abilities intimidated the younger McCartney, as

they had done Lennon.

In the Beatles

Anthology, McCartney admits that his relationship with Sutcliffe grew

particularly fraught, but Kircherr suggests it was more than that; "[...}

when Paul and Stu had a row, you could tell that Paul hated him". (Norman,

Shout!, p.90)

McCartney has

always maintained that he never wanted the job as bass player, that he somehow

got lumped with the job by the refusal of the others to take up the role. Harrison

contradicted this, recalling that “He [McCartney] went for it [the bass role]”

(Anthology)

Regardless, it

seems that McCartney viewed Sutcliffe's departure as the best possible outcome

for his and the band's collective gain...he was probably correct in his

assessment. In any case, they did have

options. Upon Sutcliffe's official departure from the group, Klaus Voorman,

their Hamburg acquaintance who would design the cover of Revolver and play bass on numerous John Lennon solo albums, asked

Lennon if he could take up the role as The Beatles bassist. Lennon turned him

down telling him "sorry mate, Paul has already bought a bass [...]" (Mojo,

10 Years, p.35).

It seems the

allegations of Lennon’s attack (as well as the predictable and highly

irrelevant claims that Lennon and Sutcliffe had a homosexual relationship) are

little but hearsay. But, they do sell books.

We will never know

the true cause of Sutcliffe’s haemorrhage, although no doubt the legend surrounding

it will continue and grow. Kircherr was convinced that Stuart had an underlying

condition that was lying in wait. That condition was possibly exacerbated by

Sutcliffe’s 24 hour lifestyle which has been documented by all those who knew

him, tutors, musicians, lovers and friends. He simply worked too hard, too

long, too intensely, smoked too much and ate and slept too little. In his last

letters home he confessed how doctors had labelled him a nervous wreck.

But what of Sutcliffe’s

musical legacy? Was he the terrible bassist some would have us believe?

Certainly, starting

out in early 1960 he was very limited and struggled his way through the

Scottish tour of May ’60. However it’s been well documented how the group went

to Hamburg a ‘banger’ (jalopy) and came home a Rolls Royce...the relentless

hours on stage turning them into a rock n roll powerhouse. If Lennon, Best,

Harrison & McCartney progressed as musicians, shouldn’t it also follow that

Sutcliffe did too? In 1960 Sutcliffe himself wrote home that the group had

improved a thousand fold since their arrival in Hamburg. (Lost Beatle, BBC 4)

The surviving tapes

that capture Sutcliffe on bass (Anthology 1) are too poor in quality to allow

any real appreciation of his ability. So, we need to examine the recollections

of those who were there.

McCartney’s opinion has been well documented,

but there were others and, contrary to the myth, many remember him as being highly

competent on the instrument.

Klaus Voorman

remembers Sutcliffe as being "[...] a heavy rock n roller. Rock n roll is

an art form, and Stuart had the feel and taste. They weren't playing anything

very complicated, and taken as a whole - feeling it and playing those few notes

- Stuart was a really, really, good bass player." (Mojo, 10 Years, p.35).

Pete Best recalled

how Sutcliffe was a decent musician with a good reputation among his Hamburg contemporaries,

and Bill Harry (Merseybeat founder) recalls

that he was quite good. Furthermore, Sutcliffe sometimes played bass in a combo

with Howie Casey (of the Seniors) in the Kaiserkeller, and they seemed to have

no issue with his competency. (Uncut March 2012).

Sutcliffe and Best may

have failed to make the grade when it came to the Beatles EMI career, in fact

Best fell at the first hurdle. However in the case of both, it’s been

convenient to excuse their treatment by the group by highlighting their musical

ineptitudes...but personal dislikes can’t be ruled out of the equation either.

The group closed rank on Best once George Martin flagged him, Sutcliffe was a

different story however; he drifted out rather than having to be pushed. He had

bigger fish to fry.

Some have argued

that he wasn’t talented enough to be in The Beatles, but his artistic pedigree

meant that he was far too talented to be in The Beatles.

John Lennon always

claimed that the best work of The Beatles was never captured, referring to

their wild, pre-EMI days. If that’s true, then he’s referring to a period when

it was more important to play, than

what you played and who heard you. The rock n roll played during this period

was uncomplicated, and if Lennon’s opinion counted for anything, and it should –

it was his band after all – then the proto-punk stage material of 1960-1962

suited the talents of Pete Best and Stuart Sutcliffe more than adequately.

Judging by the

professional critique of his surviving work, Sutcliffe would have emerged as a

major talent in the art world. In fact, had he never met John Lennon, nor

joined The Beatles, Sutcliffe would possibly have become a renowned artist. The

same is difficult to say for The Beatles, without ever having met and become

subjected to the influence of Stuart Sutcliffe.

His association

with The Beatles would probably have catapulted him to the top of the artistic

movements of the ‘60s, as he lived a celebrity life with his beautiful German

wife which would have mirrored that of the Beckham’s. Under his direction many

of the group’s album covers may have looked very different. In fact, he may

even have played on a few of them.

.jpg)

.jpg)